A group of researchers have published a very interesting paper: Click Trajectories: End-to-End Analysis of the Spam Value Chain (pdf). Using three months of spam data and by purchasing over 100 products advertised by spam emails, the researchers followed the life of a spam email and investigated where the money from purchases actually goes. They found that the people behind 95% of spam-advertised pharmaceutical, replica and software products are using just a handful of banks for their merchant services. Anti-spam efforts focus on the delivery aspect of spam, but there is potential for the quantity of spam to be significantly reduced if the banks the spammers are using are targeted.

A group of researchers have published a very interesting paper: Click Trajectories: End-to-End Analysis of the Spam Value Chain (pdf). Using three months of spam data and by purchasing over 100 products advertised by spam emails, the researchers followed the life of a spam email and investigated where the money from purchases actually goes. They found that the people behind 95% of spam-advertised pharmaceutical, replica and software products are using just a handful of banks for their merchant services. Anti-spam efforts focus on the delivery aspect of spam, but there is potential for the quantity of spam to be significantly reduced if the banks the spammers are using are targeted.

Purchasing from spam emails

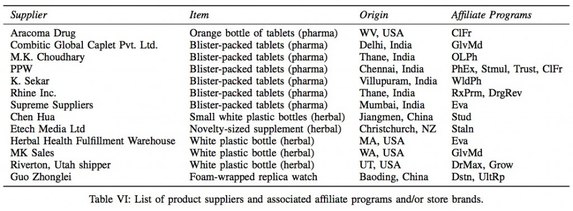

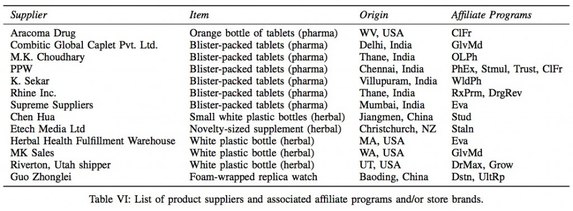

The researchers collected spam-advertised URLs and data about the hosting infrastructure and DNS of the spammed websites. They grouped the sites by content structure, category of goods and affiliate program and/or storefront brand. The most popular goods advertised in spam: pharmaceuticals, replicas and software were focused on. Pornography and gambling weren’t focused on for “institutional and procedural reasons”.

Purchases were made from each major affiliate program or store “brand” and they tried to order the same types of products from each site to try to gain insights into the differences or similarities in product suppliers that are used. A specialty issuer of prepaid Visa cards teamed up with them and let them use a different card and obtain the authorization and settlement records for each transaction. For legal reasons pharmaceutical purchases were limited to non-prescription goods like herbal and over-the-counter products. Software purchases were limited to products which the researchers already possessed a license for.

120 purchases were made, 76 of which were authorized and 56 of which were actually settled, though half of those failed orders were from one affiliate program which researchers attribute to the large order volume raising fraud concerns.

The honest spammers

A finding I found interesting from the paper is that the likelihood is quite high that you’re not going to be ripped off when ordering through spam emails.

Out of the 56 “successful” orders, 49 of the products were delivered and received. Only seven of the products weren’t delivered. Out of those seven: four sites either sent packages or said they’d send packages after the mailbox lease had ended, one said that the money had been refunded (however the refund hadn’t been processed three months later). Only two “lost” orders received no follow-up email.

The researchers explained the reasoning behind actually fulfilling orders would be so the site would get any potential repeat orders and because their relationship with payment providers could be jeopardized if chargebacks were made by customers who didn’t receive items.

Update: One of the researchers, Stefan Savage, confirmed to me that none of the Visa cards used on the spammed sites were subsequently used fraudulently. It also looks like the pharmaceutical products were legitimate. He says “we only ordered a small subset of goods so any results aren’t representative. However, we did some limited mass spec testing of a few pills against reference samples and the active ingredient was found to be the same and in a similar proportion — note we only tested for the active ingredient and didn’t look at things like binders, contaminants, etc.” Software was pirated, but malware free.

Research done by F-Secure supports this: almost all of their goods ordered from spam emails were delivered, none of the credit cards they used for orders were “stolen” and email addresses used to order the goods didn’t receive an increase in spam.

New Zealand’s fulfillment role

By volume, most herbal products shipped from the United States, but China and New Zealand were also in the mix.

A Christchurch based company turned up in results—Etech Media Ltd. Ironically, this:  is the email address listed in their whois record.

is the email address listed in their whois record.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the company in question and its owner aren’t new to the spam game. Sole shareholder and director, Shane Atkinson was fined $100,000 in 2009 for sending spam under the name ‘Herbal King’. His occupation listed in the 2005 electoral roll was “pro spammer”. The Herald “understands” that Etech Media’s office was one of the addresses searched in spam raids in 2007. In 2003, Shane admitted to sending up to 100 million spam messages a day, that spamming allowed him to have a nice car and house and said he “had no qualms about it”. “In a later interview, Atkinson said he had given up spamming.”

Perhaps not entirely?

I’ve emailed Etech Media to see if they’d like to comment.

The spam bottleneck

The researchers tried to identify bottlenecks in the spam value chain—stages where few alternative options are available and ideally where switching costs for spammers are high. Which intervention would have the most impact?

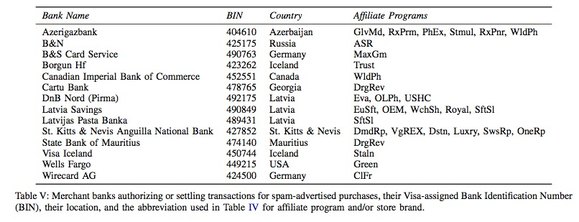

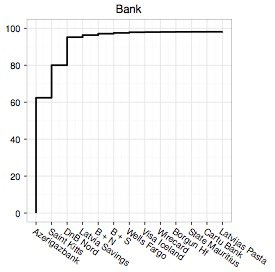

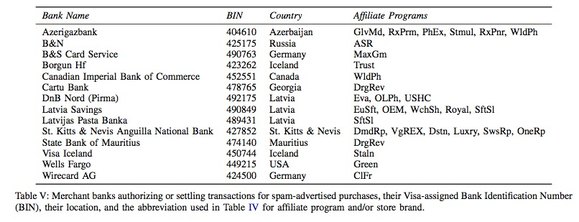

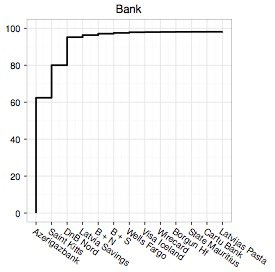

For the 76 authorized transactions, there were only 13 banks acting as “acquirers”. Herbal and replica purchases generally cleared through St. Kitts & Nevis Anguilla National Bank. Most pharmaceuticals through Azerigazbank in Azerbaijan and DnB Nord (Pirma) in Latvia. And most software purchases through Latvia Savings in Latvia and B&N in Russia.

The researchers say that the banking/payment component of the spam value chain is the most critical. Payment infrastructure has “far fewer alternatives and far higher switching cost”.

The researchers say that the banking/payment component of the spam value chain is the most critical. Payment infrastructure has “far fewer alternatives and far higher switching cost”.

- Only three banks provided payment services for over 95% of the spam-advertised goods in the study:

- There are only two main payment networks in Western countries—Visa and MasterCard.

- The replacement cost of a bank is high in setup fees, time and overhead. Acquiring a merchant account requires a lot of coordination and time. Banks used by the major affiliate programs were either still the same four months later or had changed to another one in the set identified above (only one new bank appeared four months later—Bank Standard in Azerbaijan).

Perhaps a solution is for banks that issue credit cards in Western countries to refuse to settle certain transactions with banks that support spammed goods with specific Merchant Category Codes when the card is not present. All software purchases were coded as Computer Software Stores and 85% of all pharmacy purchases were coded as Drug Stores and Pharmacies. There were some exceptions however “generally speaking, category coding is correct”. “A key reason for this may be the substantial fines imposed by Visa on acquirers when miscoded merchant accounts are discovered ‘laundering’ high-risk goods.” Similar policy has been implemented with MasterCard and Visa not allowing US-based customers to transact with online casinos.

The paper concludes: “the payment tier is by far the most concentrated and valuable asset in the spam ecosystem, and one for which there may be a truly effective intervention through public policy action in Western countries.” However spam is probably profitable for banks and payment processors too, so they might be hesitant to do anything about it.

How much spam do you receive at the moment and how much makes it to your inbox? Do you know anyone who has bought something through a spam email?

Image credit: freezelight

Perhaps he/she was meaning that you shouldn’t give people who have access to sensitive information reason to abuse it, but digging deeper, maybe the message is: treat everyone with respect no matter their position, your mood or how they treat you.

Perhaps he/she was meaning that you shouldn’t give people who have access to sensitive information reason to abuse it, but digging deeper, maybe the message is: treat everyone with respect no matter their position, your mood or how they treat you.

A group of researchers have published a very interesting paper:

A group of researchers have published a very interesting paper:

The researchers say that the banking/payment component of the spam value chain is the most critical. Payment infrastructure has “far fewer alternatives and far higher switching cost”.

The researchers say that the banking/payment component of the spam value chain is the most critical. Payment infrastructure has “far fewer alternatives and far higher switching cost”.

The

The

National’s involvement

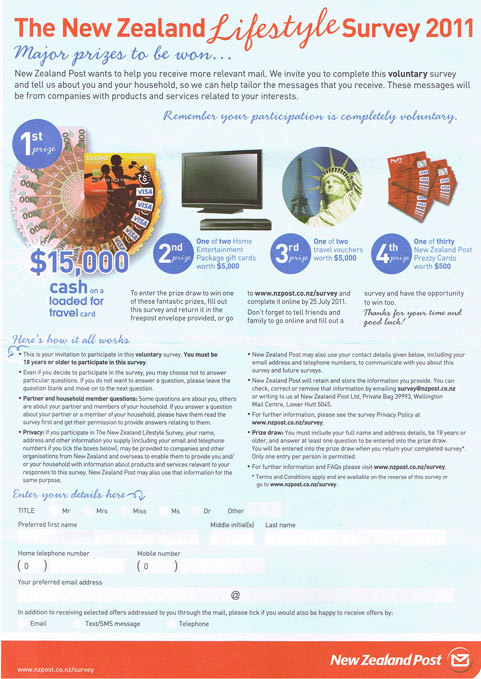

National’s involvement Today in the post we received New Zealand Post’s “lifestyle survey”, a controversial data collecting tool that’s recently been in the news because the information collected is used to market your address to other companies. The survey is sent to 800,000 households by post and 125,000 by email and asks 56 questions about various things, split into sections on your interests, vehicles, home, finances, shopping habits and travel. New Zealand Post sells names and addresses of respondents, “

Today in the post we received New Zealand Post’s “lifestyle survey”, a controversial data collecting tool that’s recently been in the news because the information collected is used to market your address to other companies. The survey is sent to 800,000 households by post and 125,000 by email and asks 56 questions about various things, split into sections on your interests, vehicles, home, finances, shopping habits and travel. New Zealand Post sells names and addresses of respondents, “

KiwiSaver will be affected by National 2011’s budget, but it will still be a worthwhile scheme for nearly everyone under 65 to be in.

KiwiSaver will be affected by National 2011’s budget, but it will still be a worthwhile scheme for nearly everyone under 65 to be in.

Some people in New York want people in the healthcare industry

Some people in New York want people in the healthcare industry

Probability

Probability