“If it didn’t exist, the government would surely invent it.”

Because it’s a great excuse for an internet censorship machine.

This isn’t a debate about whether child sex abuse is right or wrong. You know it’s wrong, I know it’s wrong, we all know it’s wrong. This is a debate about censorship.

New Zealand has an internet blacklist. A list of content that, if your internet service provider has decided to be part of the filtering project, you can’t access. Images of child sexual abuse are meant to be the only stuff blocked, but the list is secret, censorship decisions happen in private and if international experience is anything to go by, other content has a habit of turning up blacklisted.

What the filter is

Its full name is the Digital Child Exploitation Filtering System. It’s run by the Department of Internal Affairs. It’s powered by NetClean’s WhiteBox, which was supplied by Watchdog International “which provides filtered Internet access for families, schools and businesses”.

The DIA say that they’re contractually constrained to only use the filter to block child sexual abuse material.

They say that:

“The filtering system is also a tool to raise the public’s awareness of this type of offending and the harm caused to victims. The Group agreed that this particular aspect of the filter needs to be more clearly conveyed to the public.”

So basically, it’s to make it seem like they’re doing something, because it doesn’t actually prevent people from accessing child sex abuse images.

The list is maintained by three people (pdf) (mirror), and sometimes there is a backlog of sites to investigate: “The Group was advised that the filter list comprises approximately 500 websites, with several thousand more yet to be examined.”

How it works

A list of objectionable sites is maintained by the Department. If someone using an ISP that’s participating in the filter tries to access an IP address on the filter list, they’ll be directed to the Department’s system. The full URL will then be checked against the filtering list. If the URL has been filtered, users end up at this page. The user can appeal for the site to be unfiltered, but no appeals have been successful yet (and some of the things people have typed into the appeal form are actually quite disturbing).

Is my internet being filtered?

The internet of 2.2 million ISP clients is being filtered.

It’s voluntary for ISPs to participate in because it wasn’t introduced through legislation, however big ISPs are participating:

- Telecom

- TelstraClear

- Vodafone

- 2degrees

Others are:

- Airnet

- Maxnet

- Watchdog

- Xtreme Networks

I assume, for the ISPs providing a mobile data service, the filter is being applied there too.

Why the filter is stupid

Child pornography is not something someone stumbles upon on the internet. Ask anyone who has used the internet whether they have innocently stumbled upon it. They won’t have.

It’s easy to get around. The filter doesn’t target protocols other than HTTP. Email, P2P, newsgroups, FTP, IRC, instant messaging and basic HTTPS encryption all go straight past the filter, regardless of content. Here’s NetClean’s brochure on WhiteBox (pdf), and another (pdf). Slightly more technical, but still basic tools like TOR also punch holes in the filter. The filter is not stopping anyone who actually wants to view this kind of material.

A much more effective use of time and money is to try to get the sites removed from the internet, or you know, track down the people sharing the material. Attempts to remove child sex abuse material from web hosts will be supported by a large majority of hosts and overseas law enforcement offices.

It is clear that the DIA don’t do this regularly. They’re more concerned with creating a list of URLs.

From the Independent Reference Group’s December 2011 report:

“Additionally 18% of the users originated from search engines such as google images.”

Google would take down child sex abuse images from search results extremely fast if they were made aware of them. And it is actually extremely irresponsible for the DIA not to report those images to Google.

Update: The DIA say they used Google Images as an example, and that they do let Google know about content they are linking to.

“The CleanFeed [the DIA uses NetClean, not Cleanfeed] design is intended to be extremely precise in what it blocks, but to keep costs under control this has been achieved by treating some traffic specially. This special treatment can be detected by end users and this means that the system can be used as an oracle to efficiently locate illegal websites. This runs counter to its high level policy objectives.” Richard Clayton, Failures in a Hybrid Content Blocking System (pdf).

It might be possible to use the filter to determine a list of blocked sites, thus making the filter a directory or oracle for child sex content (however, it’s unlikely people interested in this sort of content actually need a list). Theoretically one could scan IP addresses of a web hosting service with a reputation for hosting illegal material (the IWF have said that 25% of all websites on their list are located in Russia, so a Russian web host could be a good try). Responses from that scan could give up IP addresses being intercepted by the filter. Using a reverse lookup directory, domain names could be discovered that are being directed through the filter. However, a domain doesn’t have to contain only offending content to be sent through the DIA’s system. Work may be needed to drill down to the actual offending content on the site. But this would substantially reduce the effort of locating offending content.

Child sex abuse sites could identify DIA access to sites and provide innocuous images to the DIA and child sex abuse images to everyone else. It is possible that this approach is already happening overseas. The Internet Watch Foundation who run the UK’s list say in their 2010 annual report that “88.7% of all reports allegedly concerned child sexual abuse content and 34.4% were confirmed as such by our analysts”.

Someone could just use an ISP not participating in the filter. However people searching for this content likely know they can be traced and will likely be using proxies etc. anyway. Using proxies means they could access filtered sites through an ISP participating in the filter as well.

It is hard (practically, and mentally) for three people to keep on top of child sex abuse sites that, one would assume, change locations at a frequent pace, while, apparently, reviewing every site on the list monthly.

The filter system becomes a single point of attack for people with bad intentions.

The DIA, in their January 2010 Code of Practice (pdf) even admit that:

- “The system also will not remove illegal content from its location on the Internet, nor prosecute the creators or intentional consumers of this material.” and that

- “The risk of inadvertent exposure to child sexual abuse images is low.”

Anonymity

The Code of Practice says:

“6.1 During the course of the filtering process the filtering system will log data related to the website requested, the identity of the ISP that the request was directed from, and the requester’s IP address.

6.2 The system will anonymise the IP address of each person requesting a website on the filtering list and no information enabling the identification of an individual will be stored.”

“6.5 Data shall not be used in support of any investigation or enforcement activity undertaken by the Department.” and that

“5.4 The process for the submission of an appeal shall:

• be expressed and presented in clear and conspicuous manner;

• ensure the privacy of the requester is maintained by allowing an appeal to be lodged anonymously.”

Anonymity seems to be a pretty key message throughout the Code of Practice.

However…

In response to an Official Information Act request, the DIA said:

“When a request to access a website on the filtering list is blocked the system retains the IP address of the computer from which the request originated. This information is retained for up to 30 days for system maintenance releases and then deleted.” [emphasis mine]

Update: The DIA says that the IP address is changed to 0.0.0.0 by the system.

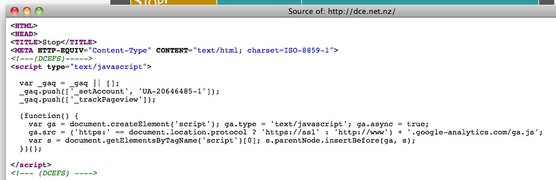

The site that people are directed to when they try to access a URL on the blacklist (http://dce.net.nz) is using Google Analytics. The DIA talk the talk about the privacy and anonymity around the filter, but they don’t walk the walk by sending information about New Zealand internet users to Google in the United States. It’s possible this is how the DIA gets the data on device type etc. that they use in their reports. Because anyone can simply visit the site (like me, just now) those statistics wouldn’t be accurate.

From the Independent Reference Group’s August 2011 (pdf) minutes:

“Andrew Bowater asked whether the Censorship Compliance Unit can identify whether a person who is being prosecuted has been blocked by the filtering system. Using the hash value of the filtering system’s blocking page, Inspectors of Publications now check seized computers to see if it has been blocked by the filtering system. The Department has yet to come across an offender that has been blocked by the filter.”

I’m not exactly sure what they mean by hash value, but this would seem to violate the “no information enabling the identification of an individual will be stored” principle.

Update: They are searching for the fingerprint of content displayed by the blocking page. It doesn’t seem like they could match up specific URL requests, just that the computer had visited the blocking page.

And, from the Independent Reference Group’s April 2011 (pdf) minutes:

“For all 4 of the appeals the complainant did not record the URL. This required a search of the logs be carried out to ensure that the site was correctly being blocked.”

Appeals are clearly not anonymous if they can be matched up with sites appellants have attempted to access.

Update: The reviewers look at the URLs blocked shortly before and after the appeal request to work out the URL if it isn’t provided.

9000 URLs!

The DIA earlier reported that there were 7000+ URLs on their blacklist. This dropped to 507 in April 2011, 682 in August 2011, and 415 in December 2011. Those numbers are much closer to the 500 or so URLs on IWF’s blacklist.

Where did these 6500 URLs disappear to (or more accurately, why did they disappear?). What was being erroneously blocked during the trial period, or was 7000 just a nice number to throw around to exaggerate the likelihood of coming across child sex abuse images (though, even with 7k sites, the likelihood still would have been tiny)?

Scope creep

Firstly, we weren’t going to have a filter at all:

‘“We have been following the internet filtering debate in Australia but have no plans to introduce something similar here,” says Communications and IT minister Steven Joyce.

“The technology for internet filtering causes delays for all internet users. And unfortunately those who are determined to get around any filter will find a way to do so. Our view is that educating kids and parents about being safe on the internet is the best way of tackling the problem.”’

Then it was said that:

“The filter will focus solely on websites offering clearly illegal, objectionable images of child sexual abuse.”

and

“Keith Manch said the filtering list will not cover e-mail, file sharing or borderline material.” [emphasis mine]

One would assume from “images of child sexual abuse” that they would be, you know, images of children being sexually abused. However, it seems that CGI and drawings (Hentai) have made the list.

From the minutes of the Independent Reference Group’s October 2010 meeting:

“Aware that the inclusion of drawings or computer generated images of child sexual abuse may be considered controversial, officials advised that there are 30 such websites on the filtering list [that number is now higher, 82 as of December 2011]. Nic McCully advised that officials had submitted computer generated images for classification and she considered that only objectionable images were being filtered.”

The arguments around re-victimization kind of fall apart when you’re talking about a drawing.

And from the borderline material file:

“The Group was asked to look at a child model website in Russia. The young girl featured on the site appears in a series of 43 photo galleries that can be viewed for free. Apparently the series started when the girl was approximately 9 years old, with the latest photographs showing her at about 12 years old. The members’ part of the site contains more explicit photos and the ability to make specific requests. While the front page of the website is not objectionable, the Group agreed that the whole purpose of the site is to exploit a child and the site can be added to the filter list.”

Clearly illegal, objectionable images of child sexual abuse? No, but we think it should be filtered so we went and did that.

Dodgy DIA

The DIA was secretive about the filter being introduced in the first place. Their first press release about it was two years after a trial of the system started. I wonder how many of those customers using an ISP participating in the trial knew their internet was being filtered during that time?

The Independent Reference Group is more interesting than independent. Steve O’Brien is a member of the group. He’s the manager of the Censorship Compliance Unit. To illustrate this huge conflict of interest, he is the one who replies to Official Information Act requests about the filter. Because the Censorship Compliance Unit operate it.

“The Group was advised that the issue of Steve O’Brien’s membership had been raised in correspondence with the Minister and the Department. Steve O’Brien offered to step down if that was the wish of the Group and offered to leave the room to allow a discussion of the matter. The Group agreed that Steve O’Brien’s continued membership makes sense.” [emphasis mine]

That was the only explanation given. That it makes sense that he is a member. Of the group that is meant to be independent.

Additionally, the DIA seems to have accidentally deleted some reports that they should have been keeping.

From Tech Liberty:

“Last year we used the Official Information Act to ask for copies of the reports that the inspectors [have] used to justify banning the websites on the list. The DIA refused. After we appealed this refusal to the Ombudsman, the DIA then said that those records had been deleted and therefore it was impossible for them to give them to us anyway. The Department has an obligation under the Public Records Act to keep such information.

We complained to the Chief Archivist, who investigated and confirmed that the DIA had deleted public records without permission. He told us that the DIA has promised to do better in the future, but naturally this didn’t help us access the missing records.”

List review

The Code of Practice says:

“4.3 The list will be reviewed monthly, to ensure that it is up to date and that the possibility of false positives is removed. Inspectors of Publications will examine each site to ensure that it continues to meet the criteria for inclusion on the filtering list.”

It’s unlikely this actually happens.

Here’s some statistics of how many URLs have been removed.

December 2011

267 removed

August 2011

0 removed

April 2011

108 removed

It’s impossible that between April and August there were no URLs to remove.

In the Independent Reference Group’s December 2011 report it seemed like the following was included because it happens so rarely:

“The list has been completely reviewed and sites that are no longer accessible or applicable (due to the removal of Child Exploitation Material) have been removed.”

The Independent Reference Group has the power to review sites themselves. But in at least one case, they chose not to:

“Members of the Group were invited to identify any website that they wish to review. They declined to do so at this stage.”

The filter isn’t covered by existing law and didn’t pass through Parliament. Appropriate checks and balances have not taken place. The DIA did this on their own.

By law, the Classification Office has to publish its decisions, which they do. The DIA’s filter isn’t covered under any law, and they refuse to release their list. The DIA say that people could use the list to commit crimes, but the people looking for this material will have already found it.

What if the purpose of the filter changes? The DIA introduced it without a law change, the DIA can change it without a law change. What if they say “if ISPs don’t like it, they can opt out of the filter”? How many ISPs will quit?

The only positive is that the filter is opt in for ISPs. Please support the ISPs that aren’t using the filter. Support them when they’re accused of condoning child pornography, and support them when someone in government decides that the filter should be compulsory for all ISPs.

Side note: why does all of the software on the DIA’s family protection list, bar one, cost money? There is some excellent, or arguably better, free software available. There’s even a free version of SiteAdvisor, but the DIA link to the paid one. Keep in mind that spying on your kids is creepy. Talk to them, don’t spy. The video for Norton Online Family hilariously and ironically goes from saying “This collaborative approach makes more sense than simply spying on your child’s internet habits [sitting down and talking — which is absolutely correct]” to talking about tracking web sites visited, search history, social networking profiles, chat conversations and then how they can email you all about them. Seriously. Stay away.

Image credit: Andréia Bohner